(This is part 2 of the series. Read the previous part here: 1)

Ruthwell Cross, inscribed with parts of the “Rood” poem.

Origins

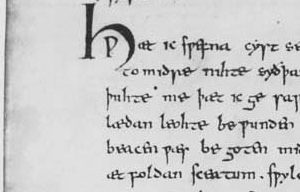

The Old English poem, the “Dream of the Rood” is fascinating on many levels. The author of the poem is anonymous, though there are a few educated guesses as to their identity. The text descends to us primarily through a single source, oddly enough a collection of Old English writings from a religious commune in the northern Italian city of Vercelli. It is written in what is called a “poetic dialect”, that is, a specialized dialect that incorporated ways of speaking Old English from every part of early medieval England (like how modern English authors can write characters that sound British, or US southern, or anything else). In fact, the “Dream” author often spells the same word several different ways within the poem.

Into the Poem

The “Dream of the Rood” concerns, properly enough, a dream. An unnamed man has a vision of the cross of Christ. It appears in two forms, morphing uneasily back and forth between the authentic, bloodstained wooden cross that Christ was nailed to and a gold-wrought, bejeweled cross like might be found in an Eastern Orthodox church (there is good evidence that the poem was heavily influenced by the eastern church). While the dreamer is witnessing this profound sight, the Rood (or cross) suddenly begins to speak to him. In historical context, this was a little unusual, but not totally unheard of. After this poem, the genre of dialogues between the cross and an important Christian figure (like Mary, the mother of Christ) became more popular. What was truly unique was a shift in perspective.

A New Perspective

The “dialogue” between the Rood and the dreamer is not really a conversation. The Rood begins to speak to the man, but the man does not answer until the very end of the poem. The Rood’s monologue is the story of the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ—but from the perspective of the cross itself. It is a brilliant way of portraying a story with which any reader of this text would have been exhaustively familiar. The reader sees the Passion story in a new light. The Rood speaks of the humiliation of being dragged onto the hill, surrounded by criminals. It speaks of the grasping, clawing hands of the “fiends” that set the cross into the hill, then set Christ upon it. When the nails are driven in, the Rood speaks of being “pierced with arrows”; when Christ’s blood spills out, it becomes like the blood of the Rood as well. The Rood laments its fate initially as an implement of death, then rejoices at the resurrection of Christ (and its own rehabilitation as a symbol of salvation).

2