(This is part 3 of the series. Read the previous parts here: 1, 2)

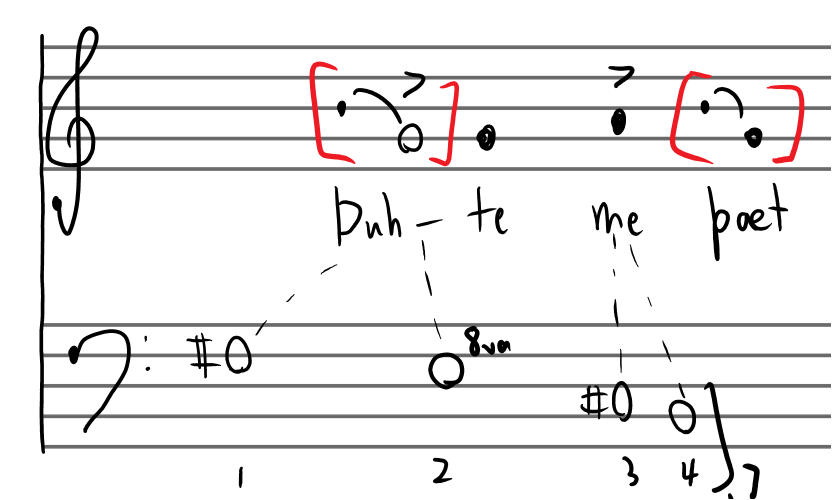

A very early sketch of the music

How It’s Made

There are few things more intimidating to an artist than the blank canvas or the empty page. Many times I have been asked, “How do you write music?” as if the process was some sort of magic ritual. It sometimes feels like that isn’t far from the truth! Creation comes ultimately from within, an outpouring of the deepest recesses of the soul, a speaking directly with the heart that it is rare to find anywhere else. Each artist takes the sum of his or her experiences and some intangible, indefinable personal affect and allows these elements to operate on each other, sometimes with the work speaking more of inward things, other times more of the world outside ourselves. When the page is blank before us, the possibilities are infinite and terrifying. The sole port in this storm of possibility is the idea on which the artistic work is based.

The Sacred Text

For my Dream of the Rood, the poem itself was the first safe haven I found for my creativity. This was what the music was about, a sacred and beautiful text centered on the sacrifice and victory of Christ upon the cross. In modern experimental art, it is not uncommon to “deconstruct” a text when using it in an artwork—to disassemble it, unmake it in some way so as to get at something underneath. What this most prominently disregards is the plain meaning of the text as well as the intent of the author (indeed, they would argue one can never know the author’s intent, and it wouldn’t matter anyway). I wanted to do the opposite. My rebellion against modern moors was to allow the text itself, its sound in the original language, its meaning, its cultural context, and its spiritual power to drive every aspect of the music.

A Weighty Task

All of this would require a daunting intimacy with the text on my part. I would need to know the poem backwards and forwards, learn the dead Anglo-Saxon language, understand the music and art of the times and the context in which the poem was written, and devise some way to translate some of this into something modern. This last task was key for me: I was not trying to make a historical re-creation—I was trying to bring the lifeblood, the very essence of the poem and its constituent culture, forward into our world. I wanted to make something new, not something old, but it would have within it a powerful lineage. Tolkien wrote once that “the old that is strong does not wither,” and I wanted to tap into that strength for a modern work of redemption. And so my preliminary research began.

1