My Cup Runneth Over

One week in Finland at a conference on the music and hymnography of the Orthodox Church is far too little, either for the loveliness of the lakes and forests or for the ancient and variegated beauty of the traditions of the Eastern Church. As part of my personal project to process the experience, I will be writing about a different aspect of my journey eastward (and westward again) each day for the next week. The unique moments and monuments of life stand as mirrors for us—we immerse ourselves in self-reflection and emerge again changed, hopefully for the better. My encounter with the east has laid before me a vast treasury of mysteries to wrestle with, to unravel. I proceed towards a spiritual, intellectual, and aesthetic denouement, but the untying of any metaphorical knot must begin somewhere. The single aspect of this unique orthodox community I miss most—miss even now, is their pervasive celebration of life in song.

In the life of the American community, even in that of the most of the more devoutly religious, is now largely bereft of communal singing. We sing in religious services the songs that we are told to sing, and we may sing together popular songs from the radio, but we do not generally sing for the sheer pleasure of singing as we gather together for a meal, or after it. My family has a tradition every Christmas season of gathering around our piano for long sessions of carols and other festive songs, but only during that time. We may laugh and tell jokes and stories (and those expressions of life-joy may deserve their own entry here at some point), but we do not sing.

My first night in Joensuu, Finland, we were hosted at dinner by the local university seminary. We began, in Orthodox fashion, by singing a blessing for our supper, and not long after the meal began, were treated to a brief concert of folk songs from various traditions translated and sung in Finnish by our hosts. This was delightful but not communal. Our conversations continued around the room until suddenly, a song was struck up among the Serbians sitting at the table behind us. A few lines were sung, some others who knew the words briefly joined in, and it died away with laughter almost as quickly as it had come. A joke then, I thought, and really not that unnatural. Then one of the Serbian composers, Milorad, walked over to the piano and began to play another tune. He got no farther than a brief introduction when the entire table behind him erupted in song. It was a rowdy thing, with vocal ornaments befitting its Balkan origins. Joie de vivre—the wine had flowed during the course of dinner but now had run dry, so as one cup was emptied, another was filled—again and again and again.

The singing was history and community, a game as well as a ritual. A soloist would often begin, only to have the rest of the crowd join in at the chorus, often in full, improvised harmony. Language was rarely a barrier for most of the others, singing songs readily in Russian, Georgian, Serbian, Romanian, Greek, Italian, Finnish, German, and English (not to mention the ancient languages used in their churches), even without always understanding them. Many of the songs were old songs: patriotic for the old country, sacred for the old beliefs, connecting to glorious and traumatic events of times past, and celebrating cultures that have an unbroken succession of song up to the present time. The air would shift slightly when a new song began, as if it remembered (in the far north of Finland no less!) the culture in question when the song was first sung. Intangibly, at the edges of the lilting melodies, you could begin to participate in the memes and metaphors and shared meanings of the community that birthed the music.

Some songs compelled us to clap along, slowly at first, then speeding up in a raucous manner—a game between the desperate soloist and the crowd that has cornered him or her, until one side gives and the room explodes once again in laughter and clapping at the madness. Other songs compelled a drone (or ison), allowing the bystanders to support the singers in some small way, to participate ourselves in the music making. With a strange unity, we could sense as a community what was required. Dramatic moments would beg the crowd to hush into silence—the gradual gathering of intensity in a song would spark clapping and stomping, as well as a myriad of vocal harmonies added at a whim, swirling into a great chaotic mass of a chord until the satisfying conclusion of the song. The soloist (or small ensemble, as the song demanded) would lead their audience like a shepherd, gathering us here, shooing us there, all the while dancing around the herd.

A rare delight—an English song I recognized—would emerge every now and again. I could finally contribute something, and while it delighted me to no end to listen to the songs of another people, singing from your own history unites you to the music and experience in a way that words fail to describe (though, of course, that wouldn’t stop me from trying). Taking the proverbial stage bares your soul to the crowd in a way that is not apparent while simply listening, clapping along, or singing the drone for the soloist. Your music-making now is personal, a connection to your community. The responsibility of being a vessel for this domestic life-joy is a burden in a way, but it is a burden that lifts as it is expended. By the end, even with mistakes and confusion (one never knows which verse will be chosen next, or even remembered), the burden has turned into an overflow of the heart: “the cup runneth over”. Now the laughter and applause is not for us as individuals, but our heritage (whether spiritual, national, or whatever else). We have shared life and thus found new life of our own.

The game continues, on and on (and not infrequently, louder and louder). After each song finishes, a chorus erupts for another: “in Finnish!” one will shout. Or requests for a specific singer will be heard (cries of “Achilleas! Achilleas!” refused to be satisfied until we were serenaded at least once each night with a song from our Greek maestro). In the Finland of summer, there is no darkness to chase away the revelers, so the celebration only ends as sheer exhaustion takes over. One by one, the celebrants slip away (often coerced into singing a farewell song, of course!) and the songs die down into quiet conversation. The ending is deceptive, of course, for a new song could burst forth unasked for at any moment, and the game will begin anew the next night, but now was the time for a communion of speech, not music. That, however, must wait for tomorrow.

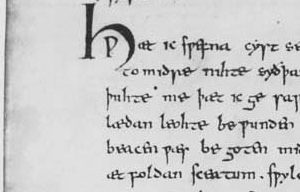

Our game of songs from our second night in Joensuu, at a reception of the regional council of North Karelia.

Pingback: Gazing East, Part II | Neuestalgia()

Pingback: Gazing East, Part III | Neuestalgia()